USB-C for Engineers, Part 3

USB Power Delivery is a new specification that enables new functionality for the USB-C connector. In this part, I'll go over the benefits of the specification and details of its implementation.

USB Power Delivery Rev 3.0 is included in the USB 3.1 specification, which you can download from here. The spec has three major purposes.

- Enable a much wider range of power options

- Provide a side-band channel for standard and vendor defined messaging

- Allow the use of Alternate Modes.

Power

Under the USB-C specifiction, without Power Delivery, the maximum power allowed is 15 W. Additionally, the only allowable voltage for Vbus is 5 V. With power delivery, the maximum allowed power increases to 100 W with a maximum voltage of 20 V. A Power Delivery Explicit Contract overrides any other means of determining power levels, as shown in the USB-C spec.

In addition to fixed voltage supplies, there a few other options (section 7.1.3). Variable supplies are "very poorly regulated Sources". Battery supplies expose a direct connection to a device's battery. Programmable supplies expose a well regulated, but adjustable voltage output. Regardless of its other capabilities, any Source must provide a fixed 5V supply.

Side-band Communication

Vendor Defined Messages (VDMs) allow devices to exchange information not defined by the USB specifications. There are structured and unstructured VDMs. Unstructured VDMs provide 14 bits in the header to use for your own purpose, along with up to an additional six objects, each 32 bits long.

Structured VDMs are used to send information about, and agree on, Alternate Modes. For example, under DisplayPort over USB-C, Hot Plug Detect (HPD) is sent as a structured VDM.

Alternate Modes

Alternate modes let you use some of the pins in the USB-C connector for your own purposes. The most common alternate mode is DisplayPort over USB-C. A spec for HDMI over USB-C has also been released. Modes are distinguished with the Standard or Vendor ID (SVID), a unique 16-bit number assigned by the USB-IF (section 6.4.4 of USB-PD spec).

For a full featured cable, you can reconfigure the four SuperSpeed pairs and the Side-Band Use (SBU) pair. If the device has a "captive cable" (cannot be unplugged) or has a "direct connect application" (plug orientation is otherwise assured), three more pins are available. These are the two pins opposite the USB2.0 D+/D- lines and Vconn. You can learn about the connector requirements in section 5.1 of the USB-C spec.

BMC Communication

As of Rev 3.0 of the USB Power Delivery specification, only Biphase Mark Coding (BMC) over USB-C is supported. The physical layer is defined in section 5 of the spec. BMC uses a single wire to communicate between two devices, up to two cable plugs, and up to two debug devices. All communication is half duplex with collision avoidance and 4b5b encoding for DC-balance. The data rate is about 300 kbaud. CRC32 is used to ensure data integrity.

BMC is a version of Manchester coding. There is a transition at the start of every unit interval, and a second transition to indicate a 1. A preamble is used to train the receiver on the exact bit rate. This is followed by a sequence of K-codes that form a Start of Packet (SOP*), which is essentially an address. Then the data is sent, along with a CRC, then finally an End of Packet (EOP).

The SOP* can be one of a few options. SOP addresses the other device, and only Power Delivery Capable Sources or Sinks can respond. SOP' (aka SOP Prime) is used to communicate with the cable plug, such as in the case of an electronically marked cable. SOP'' (double prime) is the other cable plug. SOP'_Debug and SOP''_Debug are undefined, but I'm assuming they will be used for debugging purposes based on the name.

For symbol and bit ordering, everything is least significant first. For an SOP* sequence, K-code 1 is sent first. For each K-code, bit 0 is sent first. When transmitting 16-bit headers or 32-bit data objects, the least significant byte is sent first, and the first bit of the 4b5b nibble transmitted is bit 0.

Section 5.6.2 provides the details of the CRC-32 calculation. I've used this calculator to double check CRCs I've received. Be sure to select Hex and reorder your bytes if needed.

USB-PD Protocol

Everything that happens with USB Power Delivery happens with messages. There are three types of messages.

- Control Messages (no payload)

- Data Messages (short payload, up to 240 bits)

- Extended Messages (bigger payload, up to 2080 bits)

All messages have a 16-bit header. The structure of the header is defined in section 6.2.1. A control message is just this 16-bit header. If bit 15 is set, the message is an extended message. If bits 14..12 are not zero, it is a data message. Otherwise, it is a control message. The other bits of the header determine the current power and data roles of the sender, specification revision used, and a 3-bit rotating message id. The bottom four bits are the message type. Depending on if the message is control, data, or extended, you will need to check a different table.

Most of the control messages (section 6.3) are self explanatory. The most common control message is GoodCRC. It is sent in response to every correctly received message, and has to start within 195 microseconds. Get_Source_Cap is used to request the power source capabilities of the other device. PR_Swap, DR_Swap, and VCONN_Swap are used to swap power, data, and Vconn providing roles, respectively. PS_RDY is used to indicate the power supply is ready.

The data messages (section 6.4) are more complicated. Each data message has at least one 32-bit data object following the header. Capabilities messages are used to share the port's options for power. This must include a 5V fixed supply, which is always the first option, and up to five additional options. Fixed supplies are first, lower to highest voltage. Next are battery supplies by minimum voltage, then variable by minimum voltage, then programmable by maximum voltage, all lowest to highest voltage.

The Request data message is used by a Sink to request a power option from the Source Capabilities list. The Sink then provides some information about how it will use the supply, including if it supports USB communications, USB Suspend, and its maximum and nominal current or power usage.

Vendor Defined Messages were discussed above. BIST is used to enter Built-In Self Test mode. Battery_Status and Get_Country_Info are self-explanatory. Alert is used to indicate a change of status.

Extended Messages (section 6.5) are new to Rev 3 of the spec. They are used to send a lot more information than is possible with just Control and Data messages. This can include hardware and firmware version IDs, manufacturer strings, additional battery capabilities, security information and authentication, and even firmware updates.

Implementation

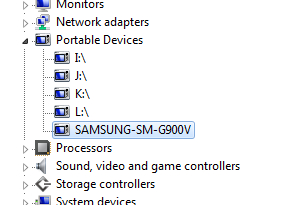

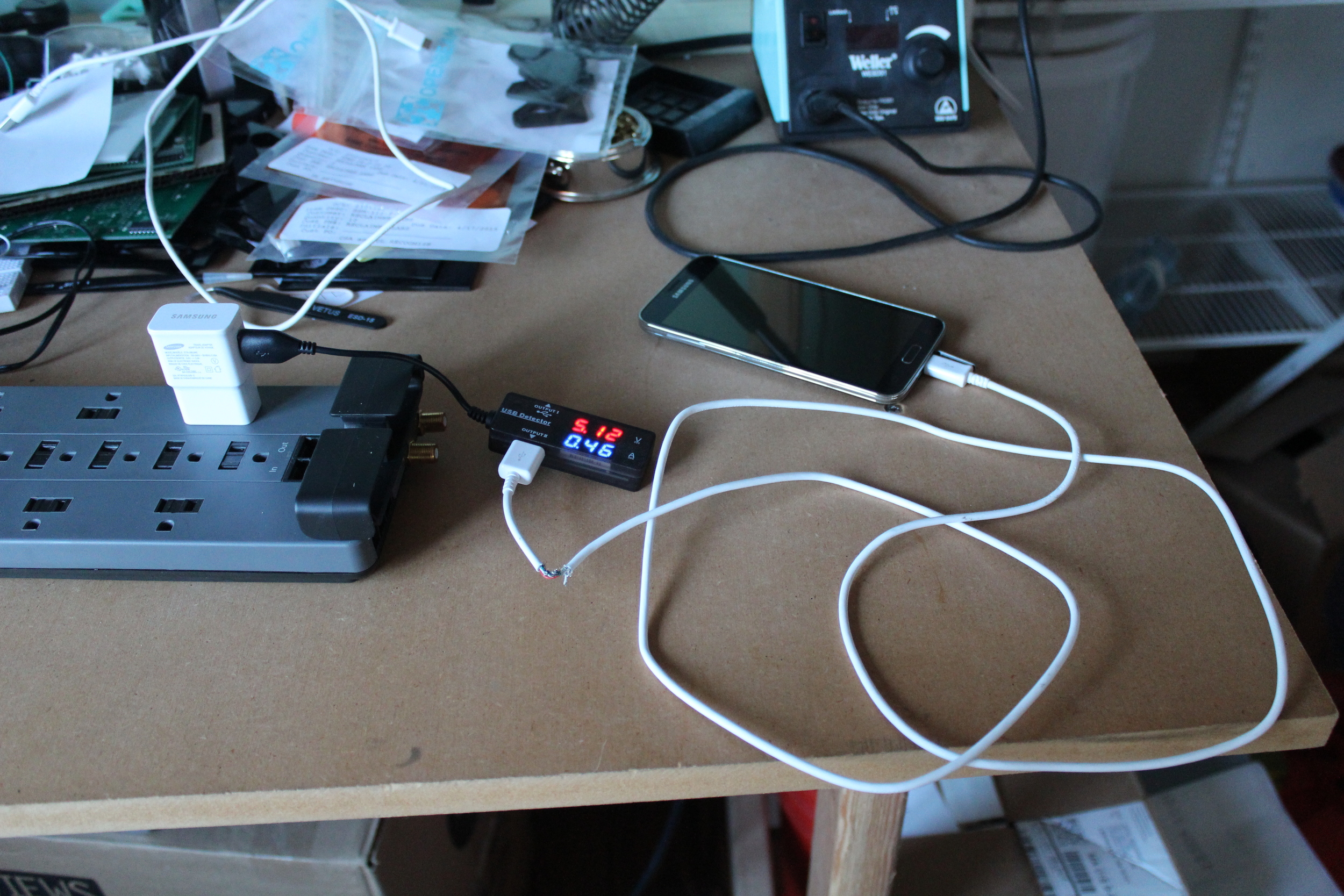

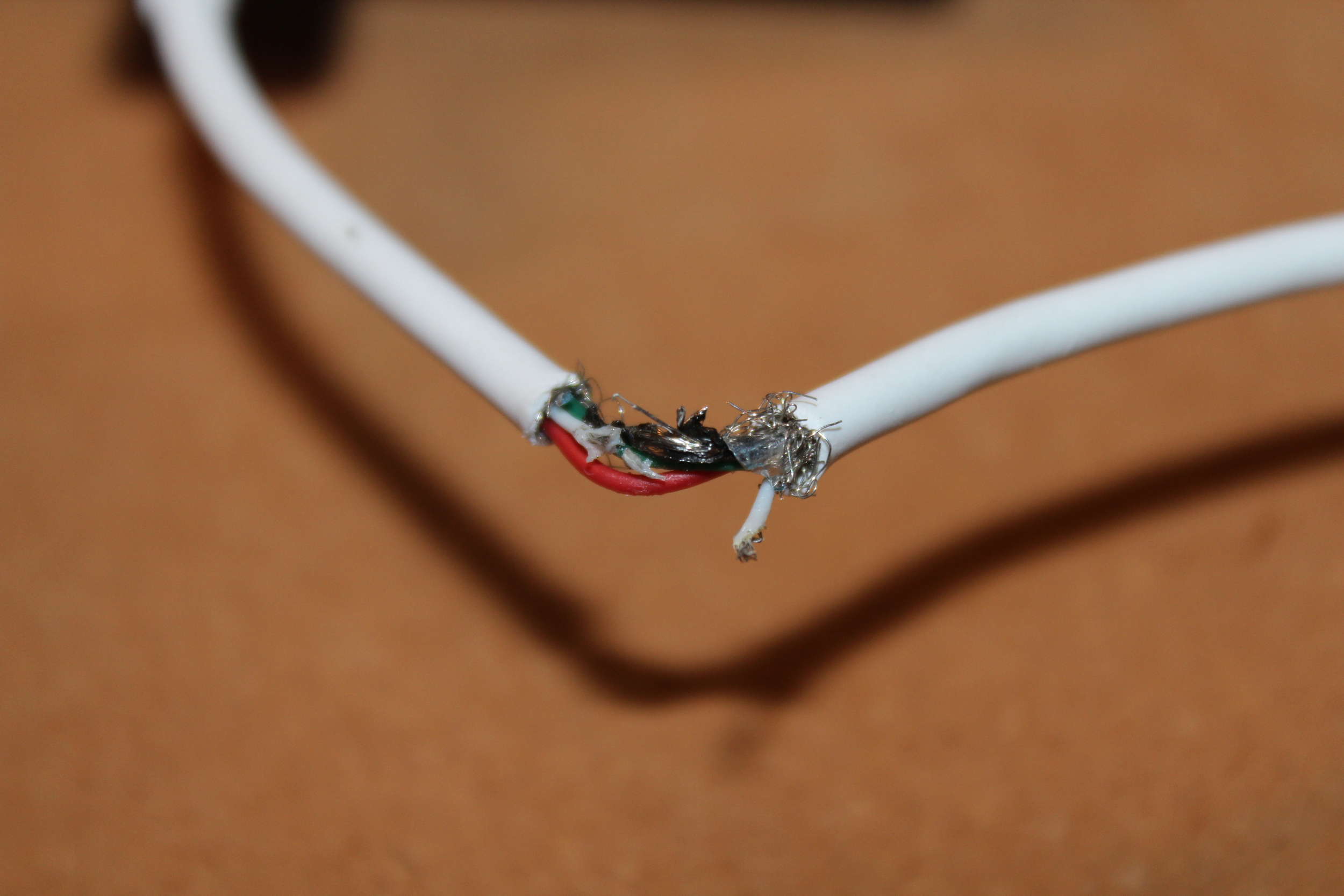

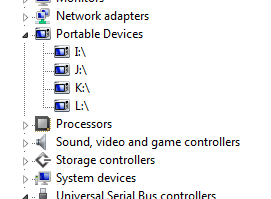

I've been putting together some code to implement the USB Type-C and USB Power Delivery specs. As of the time of this writing, it is still early days. I started with the Google Chromebook code base and ported it to C++. After 4000 to 5000 lines of code, including a 1200 line state machine with 29 states, I have something that might be a bit messy, but is starting to work.

Last week, I used this code to get 14.8 V out of my Macbook charger, using my FUSB302 breakout board. The code ran on an Arduino and used 70% of the program space. I've been pulling the Arduino-specific functionality out into separate functions. My intention is to create a more standalone library suited for embedded development on a variety of platforms. Any help and suggestions are appreciated. You can find me on Twitter, among other places.